(Updated 8/10/2014)

To read PDF (portable digital files) documents, you will need Acrobat Reader. It can be downloaded for free at: http://get.adobe.com/reader/

TWA’s Director of Customer Service Program

By Jon Proctor

The origin of the DCS position at TWA dates back before the widebody era, and can probably be credited to the Director – Passenger Service (DPS) at Continental Airlines, a position that began with that carrier's Boeing 707 "Golden Jet" service in 1959. The DPS position was somewhat different, in that he (all were men) actually collected tickets on board. With Continental's "instant boarding" program, passengers were able to board a flight without a ticket and purchase one after departure. It is not clear how much authority the DPS had over the four "hostesses" in the cabin, but the position was heavily marketed in Continental's print advertising and included reference to the fact that he had his own "radio-telephone" system available to make airline, hotel and car rental reservations. (Later, when Continental inaugurated its first 747 service, the airline actually assigned two Directors on each flight, although by then they may have discontinued ticket collection. It is not clear when the position was dropped altogether.)

Other than Boeing 707s versus DC-8s (and later, Convair 880s), none of the airlines had much of a competitive edge. Meal service was enhanced, as with TWA's famous Royal Ambassador Service that was introduced on international flights soon after the jets arrived, and terminals were upgraded with loading bridges – or Jetways – along with other amenities, but only Continental had upgraded its in-flight image with the DPS.

We can thank Continental Airlines for planting the DCS seed at TWA.

At TWA, our Terminal Service staff began looking for that competitive edge and proposed replicating Continental's DPS program by putting a member of management on every 707 flight in order to provide the highest possible level of passenger service. For lack of a better title, the DPS designation was used in the proposal. Three station supervisors were selected to test the program. Among them were two gentlemen who would later experience a close relationship with our DCS program, Jim Dolin and Dick Veres.

Armed with an Official Airline Guide (OAG), they met and greeted passengers, assisted with hotel and car reservations and made appropriate on-board announcements, much the same way as their counterparts flying Golden Jets

Jim Dolin plays DPS in the Boeing 707 mockup at Kansas City.

The DPS program did not fly at TWA for one basic reason: financing. The company was still recovering from the end of the Howard Hughes days and trying to catch up with the larger jet fleets of American and United.

Fast-forwarding to the early 1970s, TWA leapt into the widebody jet era as the second carrier to begin 747 service, following Pan Am by only a few months. With this huge airliner that more than doubled passenger capacity over that of the 707, a decision was made to add a new cabin attendant position; enter the Flight Service Manager. On international flights, the Purser position remained as well. Early TWA 747 flights were, to put it kindly, a bit disorganized. After a few months, it became obvious that the transition from narrow to widebody needed more than an upgraded Purser to pull it all together.

Two of those pictured - Ernie Lorenzen and Des McGuire - would go on to become DCSs.

Top Row: Ernie Lorenzen, Les Miller, Des McGuire

2nd Row: Jerry Nichols, Jack Taylor, Hal Brown

3rd Row: Fred Pereira, SAS F/A, Don Green (TWA safety instructor)

4th Row: Suellen Schmanke, Dee Sagers, Air Canada F/A

5th Row: Bea Elosser-Tuttle, Georganne McNab, Sandy Christman-Hincks, Karen Merry, Pam Beckman (Beatty) (deceased), Ann Robards, Nina Peltzman-Wolff, two Boeing instructors; the one on the left resembles Ed Frankum!

The number 5 on the steps refers to aircraft line number 5, which was N93101. At the time, it was still in the test flight program, and did not have a fully furnished interior; note the bare passenger door above Ernie, Les and Des. Also, the word EXPERIMENTAL can be seen next to the number 1 door.

TWA management turned to the same solution it had long relied upon, yet another task force! This one was named the 747 Cabin Attendant Supervisory Task Force. From that exercise came a proposal to implement the pre-jumbo plan for a management representative to be placed on each 747 flight, and to do it as soon as possible in order to "improve the service level on the B747 flights."

By the summer of 1970, the easy decision had been made. Yes, we would implement the "747 Supervisor" program, hopefully by June 8, because the first class was to graduate on June 4. Then followed the more difficult challenge: how would this program interface with In-Flight Service management, as we know it today? The battle lines were drawn. Dick Veres became the manager of 747 In-Flight Service based at JFK where the supervisors would all be initially based. However, there was already in place a management team in charge of the domicile led by Anita Boylan.

Many questions were left to be answered as the actual 747 Supervisor position evolved:

• Permanent policy regarding selection of candidates

• Moving expenses for successful candidates

• Finalization of job duties

• Uniform

• Training program

• Scheduling

• Air-to-ground radio (which Continental had; we never did get them)

• Liaison with Passenger Service employees

• Ambassador Club accesses

• Expense reimbursement

• Equipment (attaché case, validators, ticket stock, etc.)

• Business cards - Title??

• Reservation "free sale" definition

Somehow we got up and running, and made peace with entrenched In-Flight management folks. The turf battle at JFK resulted in a new position: Manager – 747-In-Flight Service, filled by Dick Veres. Group Supervisor positions evolved, and were awarded to familiar names including Ron Green, Rod Gaines, Leif Hansen, Ralph Wilson and others. Gray business suits became uniforms. Once established, the title of Director – Customer Service came into being as our group began establishing a relationship with not only the cabin attendant crew, but also with three men (yes, they were all men back then) on the upper deck, including the one really in charge, known simply as "Captain." This presented one of the major challenges confronting every DCS as he or she began a new career. Some of the stories regarding this transition have become folklore and are repeated annually at DCS reunions.

(Continued below)

The Right Time By Nancy (Ricioli) Asay Class 70-1 The turmoil decade of the 1960s was over. Women had burned their bras and popped birth control pills like candy as their independence grew with the unveiling of the ’70s. Bell-bottoms, mini-skirts, false eyelashes and long beautiful hair were the new rage. Women were changing, but corporate America was still owned by men. We were able to hold small jobs, but unable to reach much higher, and if perchance we happened to take a step up the ladder, our salaries did not match that of the men for the same work performed. The airline industry was changing too. The ’70s opened on a mixed note for TWA. The jumbo-jets had arrived, and the airline had become a truly global carrier. It was moving from the streamlined narrowbodies into the world of widebodies. The first 747 had just rolled out of the Boeing’s Everett, Washington, plant to be delivered to TWA. On a bitterly cold and gray January 7, 1970, the huge jetliner emerged from overcast skies of Kansas City International Airport, and the gathering of newsmen and TWA corporate officials suddenly forgot the below-freezing temperatures and bolted for better vantage points as the world’s largest commercial jetliner, TWA’s first Boeing 747 swept over the runway’s threshold and floated to a touchdown. With the reverse thrust of the engines the plane finally stopped, to an up-roaring applause as thousands of cameras flashed. This was like no other aircraft—it was the biggest, most beautiful, and absolutely mind-boggling. The 747’s huge hump was its distinguished feature. It measured 231 feet in length with a wingspan of 196 feet. The length of the fuselage was greater than the distance covered in the Wright brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk. Its fuel capacity was sufficient to power a six-cylinder car around the equator 29 times. First class held 58 passengers, and the aft three compartments on the main deck held 284 coach seats—a total of 342 passengers (a small town) could fly together transcontinental or across the Atlantic. I was a flight attendant supervisor at JFK when Chuck Butler, Manager of Flight Attendants, called me into his office and informed me I had been chosen to participate in the FAA Certification to approve TWA’s 747 to fly commercially. I was thrilled. The FAA required that the aircraft be evacuated in a specified time frame. The management crew went through extensive 747 emergency training to prepare. The jumbo was hauled into a Kansas City hangar. Church groups had been invited to tour the 747. They had no inkling they would be participating in an actual evacuation to certify TWA’s aircraft for commercial travel. We boarded the excited groups, closed the cabin doors, gave departure announcements, and began a beverage serve, when suddenly the evacuation alarm system belted its high, pulsing shriek and the cabin went black, just before the emergency lights flashed on. The crew went into evacuation mode, flinging doors open as evacuation slides popped open in clouds of dust, and inflated into colossal slides. The crew began evacuating the startled people and successfully passed the FAA evacuation test. This was the first baby step for the monstrous plane to enter the world of commercial travel The second step was the 747 route proving flight. This would be the plane’s first official visit to major stations in the United States and Europe that would be served by the jumbo. This would enable ground personnel to actually see the plane and receive hands-on training during its short layover at their station. The historic flight was to be piloted by Captain J. E. Frankum, vice president of flight operations. Harriet Korn, manager of in-flight service procedures, would also be on the proving flight, part of the handpicked management crew. Chuck Butler informed I had been selected as well. I was speechless. On the frigid morning of February 2, 1970, Captain Frankum piloted TWA’s 747 Proving Flight up and away from MCI, bound for LAX as the entire airline followed our flight plan. Airports hosted elaborate celebrations in the terminals when the aircraft arrived. Ground personnel eagerly jumped aboard with thick 747 procedure manuals tucked securely under their arms for their night crash course.

At London, a few of the crew wave from the steps. At European terminals, crowds estimated at up to 20,000 stood in freezing weather for hours, waiting to be the first to see TWA’s Jumbo jet (as the media had nicknamed it). Switzerland presented the crew with a jumbo 747 made of chocolate, Spain presented Captain Frankum with a beautiful Persian carpet for our training center, and Paris gave us the keys to the city.

Accepting chocolate cakes on behalf of the 747 route proving flight crew at Frankfurt: Bea Elosser-Tuttle, Harriett Korn Yelin, Nancy Ricioli Asay, Marilyn Veyzosi. Security guards surrounded the plane the moment we stepped off the aircraft. When we moved from the security zone into the media area, reporters were quick to stick microphones in our faces as news cameras recorded our every word. And then, armed guards lead us away through the crowds, who with outreached paper and pen in hand begged for our autographs. Can you imagine people wanting our autographs? At the time we chuckled at it all. We did not realize then, we were a part of history making; the age of the widebody jet was about to change airline travel forever.

The entire route proving flight crew pose at Lisbon

At a crew dinner in Paris. From bottom right, counter-clockwise: Marilyn Vezzosi (facing away from the camera), Jim Tighe, Bea Elosser-Tuttle, Gordon Granger, Bernie Gosey, Tom Crimmens, Nancy Ricioli Asay, Billy Williams, Tony Gatty, Marv Horstman, Guenther Zoeller, Harriett Korn, Ed Frankum, Nina Peltzman

With the passing of the FAA certification and proving flight, TWA’s 747 began commercial travel. Inaugural of 747 service across the United States, the first in the industry, came on February 25 when Captain Frankum (along with Captain Billy Tate as first office and Jack Hough as flight engineer) once again was at the control as Flight 100 departed Los Angeles for New York with 254 passengers aboard. I was assigned to complete on-board, in-flight service studies and help the flight attendants understand the overwhelming 747 emergency and service procedures that were required on such a mammoth aircraft. Ten cabin doors, and each with its complex procedures for closing and opening. When management was not on board, flight attendants often became flustered with the procedures. As a result, emergency slides were inflated, canceling many flights. TWA’s 747s were losing money. TWA Corporate finally realized that an in-flight management position was needed to oversee commissary provisioning, customer service, ticket sales, supervision of flight attendants and even our customers’ baggage handling upon arrival. A new position was to be created. We were initially to be called TWA 747 Supervisors, shortly thereafter, renamed director of customer service, to be known by all as the DCS. This core of management personnel was tasked with bringing 747 service out of the red and into a black profit margin. A job-opening announcement flashed across the wires and drew more than 2,000 applications for 18 openings in the first class. This was the job of my dreams. I thought I was exceptionally qualified. Sadly, upon reading the job description I lacked the gender qualification: I was a female and you had to be a male. I had almost given birth to the 747, and now, as a woman, I would not even be given the right to interview for the position! What a grave violation of Women’s Rights, I thought. A day later, I walked into Chuck Butler’s office with application in hand and laid it on his desk. “I am applying for this position; are you behind me?” He cracked a huge smile and asked, “What took you so long?” We both expressed amusement at the gender qualification. I arrived in Kansas City the next morning at 8 a.m. and went directly to the Jack Frye Training Center where the interviews were being conducted, a process already in progress for several days. The panel interviews, conducted by nine men, lasted up to a half-hour, but many were much shorter; successful candidates would be notified by mail. The waiting room was packed with male candidates. I walked into the room as all eyes watched me sit and cross my legs. I pulled out a book and began reading. The men were perplexed. Finally one brave soul piped up and asked, “Why are you here?” adding, “You’re a girl!” I put my book in my lap, turned and answered, “To get the 747 supervisor position,” and began reading again. The room burst into laugher. I did not know if they were laughing at me or the poor soul who instantly turned beet-red, zipped his mouth and did not utter another word. When the door opened and his name was called, I looked at him and said, “Sir, good luck." He gave me a nervous smile and added, “Good luck to you too!” I had been sitting in the waiting room all day and was the last to be interviewed. It was 5:30 p.m. The door opened and my name was called. After being interviewed for an hour and a half, a panel member asked if I had anything to add before I was excused. “Yes,” I replied, adding “If the only reason I do not get this job is because of my gender, then I have not failed; TWA has failed as an airline.” I was politely excused and told to wait outside in the hall. Ten minutes later, nine men filed out with enormous smiles and congratulated me on being the first woman hired as a 747 supervisor. “You have a big burden,” one of the men mentioned. “You must prove to TWA that a woman can handle the job before we will consider hiring more women for the position.” A wire was sent out that night, stating that females were being considered for the position. A few more all-male classes were assembled, but a new door opened in the airline industry and many talented women followed, warmly welcomed into a position that broke the gender barrier early on. And the rest is DCS history. |

(Contined from above)

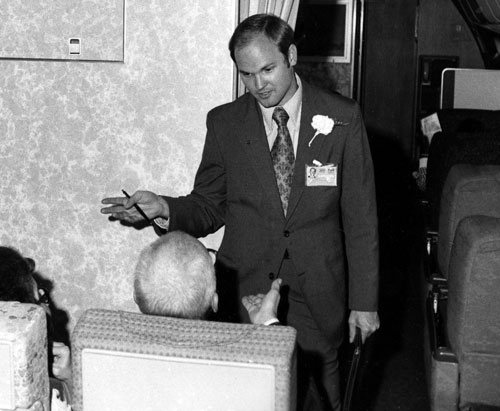

Roy Kral and Bob Anderson aboard Flt 1 JFK-LAX July 10, 1970.

I applied for the position in 1970 and was turned down, being covertly informed that my weight was a major factor in the decision. I became even more interested in the job when I learned that the two DCS recruiters, Hank Krueger and Bob Leonardt, had both abandoned their positions in favor of the DCS title!

The widebody DCS diploma.

After leaving TWA briefly and losing some weight, I was finally selected for DCS position in mid-1971 and began training at Breech Academy on July 19. My class was generously sprinkled with furloughed pilots, a flight attendant and two pursers, plus representatives from Passenger Services. All of us were assigned to JFK, although by then, as I recall, a small DCS base had opened at LAX. My first "observation" flight, from JFK to LAX, was under the expert tutelage of DCS legend Bob Anderson, a former TWA sales rep, who could steal business from the competition like no one else. Among the other things I recall is the fact that he and I spent some time after the flight obtaining ticket endorsements from international carriers that had suffered substantial revenue loss thanks to Bob's persuasive powers with customers. One family of four, who were connecting to Hong Kong on BOAC, switched to TWA when Bob convinced the mother that her two children would be happier with us where they could watch a movie; at the time, BOAC was not showing films on its trans-Pacific flights; Bob knew every trick.

About this time, a great story on the DCS program appeared in our on-board TWA Ambassador magazine, ghost-written by Charlie Betz. Click here to read the story.

I flew out of JFK from September 1971 until the following April, when a DCS domicile at Chicago-O'Hare was formed in anticipation of the L-1011 introduction; ORD-based cabin crews were to fly all 1011 time initially, with service due to start in June.

I believe there were already five from our group at ORD (Penny Donahue, Dale Kreimer, Hank Krueger, Bob Henderson, and Bob Green) on somewhat of an ad-hoc basis, flying 747 Las Vegas turnarounds and two-day trips to LAX and SFO, with other DCSs temporarily assigned to fill in as needed. Bruce Megenhardt and I transferred to ORD and began working 747 trips.

As the L-1011 schedules came on-line, the Chicago DCS domicile grew quickly under GM Diane Croll and Group Supervisor Ralph Wilson. ORD was a great base, and our group held the distinction of being the only domicile that cabin attendants actually supported when polled in a survey. Naturally, some eyebrows were raised by those who wondered just exactly why the ORD domicile liked us while the others did not; fraternizing had nothing to do with it, of course … .

DCS Hank Krueger chats with customers on the June 25, 1972 L-1011 inaugural flight.

At the program's peak, there were DCS domiciles at JFK, BOS, ORD, LAX, and SFO. The narrowbody DCS Program evolved, adding an MCI base. Narrowbody supervisors undertook a slightly different course, with much less visibility on flights and more emphasis on market segments, hence their titles of "Market Segment Director of Customer Service, per the below certificate.

By the end of 1974, TWA was flying 19 747s and 24 L-1011s. Although six more TriStars would be added in 1975, an equal number of 747s departed for Iran as our airline faced bleak financial times. Throughout the DCS program, furloughs were avoided by very creative scheduling that included bunching vacations into off-peak seasons ... Does anyone remember "Kitzmiller's Peak?"

DCS Jim Tucker and his outstanding ORD-based 747 cabin crew

I left the program in April 1974 to take a corporate staff position at 605 Third Avenue, New York, rejoining the DCS ranks almost exactly two years later and resorting to a lifestyle that I'd become accustomed to. Flying once again from JFK, it didn't get any better than this, and I expected to remain a DCS until retirement.

That plan lasted less than six months.

We were all holding our breath during that spring of 1976 as talks between the flight attendant union and TWA management broke down. I was on a San Francisco layover June 4, when the 30-day cooling off period ended at midnight with a contract agreement. As I checked in at operations the next morning, an agent told me to call the New York In-Flight office. The news was good and bad; we had a contract, but at a price. The DCS program was to be disbanded. Soon, I would be a flight attendant supervisor, mostly on the ground, along with my fellow DCS comrades. By mid-September, it was all over.

Several of us had found an extension of the program with Saudi Arabian Airlines, on temporary assignments completing a similar job description as In Flight Supervisors (IFS), based at Jeddah and later London. Click here for a review of this program.

In retrospect, we can look at the other airlines. Continental, American and United all removed supernumerary positions from widebody jets. Perhaps we had completed the mission. By then, routine service aboard the jumbos was firmly in place. Coach lounges had come and gone, along with most of the frills. Nine-abreast seating on the 747 gave way to ten across, while the L-1011s increased from eight- to nine-abreast. The realities of airline economics in the '70s and beyond squeezed every dollar of profit. We were among the casualties. And yet most of us would not trade the experience for anything. We grew from it, and even the final chapter was a character builder.